PUBLISHING KING LEAR

31 MARCH 2020

Literature in Lockdown - 1

As London settles into a period of restricted movement, we look at some documents from the Stationers' Company Archive, which show us how writers, printers and publishers have responded to similar crises over history.

We start with the publication history of Shakespeare's King Lear.

If you're hoping to use a self-isolation stint to unleash your creativity, one of the more optimistic memes going round is the story that Shakespeare wrote King Lear during a period of lockdown. 1603 saw one of the most virulent outbreaks of plague in the history of England, leading the privy council to decree that theatres should shut once the weekly death toll from plague rose “above the number of 30”. In July 1606, another outbreak closed theatres for months. It’s highly likely that Shakespeare used such periods of enforced closure to work on material for his company to perform once things got better.

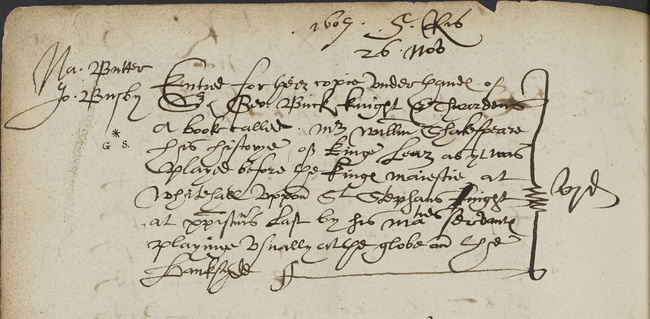

While we can't be sure of exactly when King Lear was written, the Stationers' Register for this period does give us an unusually precise date for a key performance. The entry of copy, made on the 26th of November 1607, tells us that it was 'played before the King Majesty at Whitehall upon St Stephen's night at Christmas last' - i.e., the 26th December, 1606.

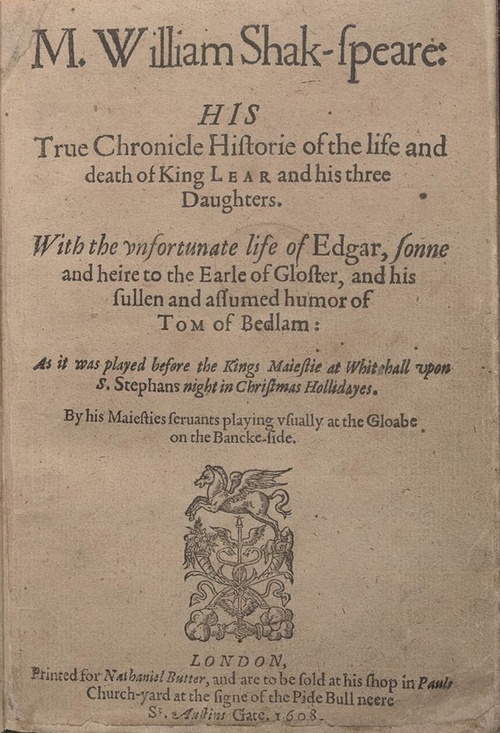

The printing rights for King Lear were entered to two Stationers named Nathaniel Butter and John Busby. Butter is a significant figure in the history of the Stationers' Company, and indeed in the history of printing. An early publisher of cheap pamphlets and plays, he made a name for publishing and promoting corantos, early forerunners of modern newspapers, in the 1620s. Busby’s name has come to be associated with the publication of pirated texts and ‘bad’ quartos.

There are significant differences between the quarto published by Busby and Butter, and the folio text published some sixteen years later. Scholars have offered various explanations: that this was due to the inexperience of the printer, Nicholas Oakes, in calculating the number of words per page; that the divergences indicate different staging practices; or that Shakespeare himself revised his play from the ‘foul papers’ (working draft) used for the first printing. However, despite the discrepancy, this earlier version is generally not considered a ‘bad’ quarto (an unauthorised copy transcribed from memory by an audience member or actor). The details given in the entry of copy, and on the title page of the quarto, indicate that the text was printed with the permission of Shakespeare and the King’s Men.

Typically, plays were only printed when they were unlikely to generate more ticket sales. The fact that King Lear was printed only a year after its royal performance has thus led some Shakespeareans to suggest that the play was not popular at the time - something to bear in mind if your own lockdown efforts are not as enthusiastically greeted as you might hope. Various versions of the play subsequently had extremely successful performance runs, of course, and many consider Lear Shakespeare’s finest play. An interesting footnote: between 1810 and 1820, the play was banned from performance, as the reigning monarch, George III, suffered recurrent manic attacks, and the portrayal onstage of a deranged king was considered insensitive.