FORERUNNERS TO COPYRIGHT: THE STATIONERS' REGISTERS

22 JANUARY 2021

This Day in the Archive: 22 January

With so many changes happening around us, from fluctuating infection rates to alterations in our centuries-old Hall, it can help to find a wider sense of continuity with the past. The Stationers' Company is extremely lucky to have an extensive Archive dating back to the granting of its Charter, with relatively few breaks in its records. Over the next few months, I'll be making occasional forays into the Archive to highlight records of events in the Company's history that happened 'on this day'.

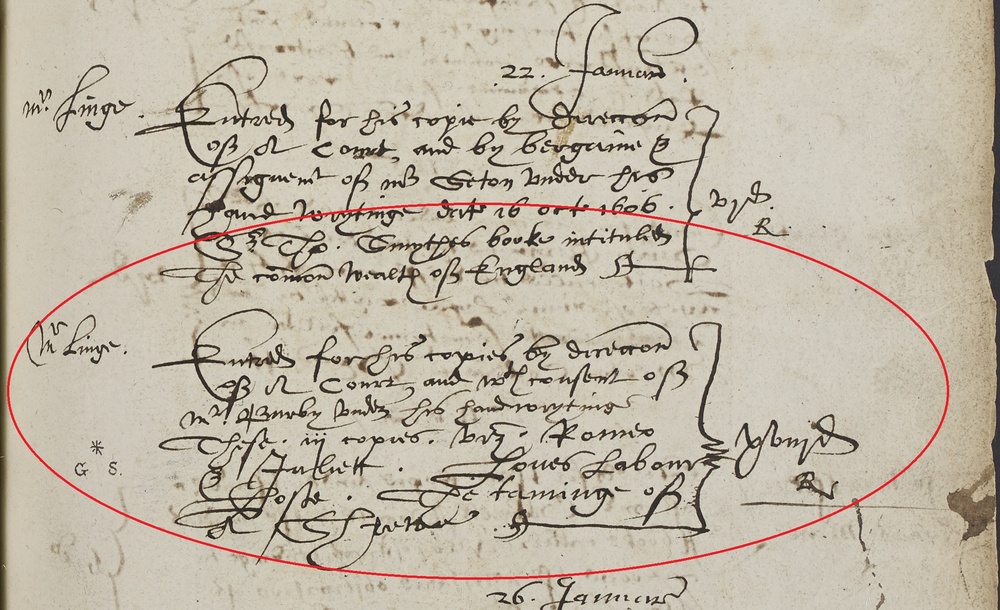

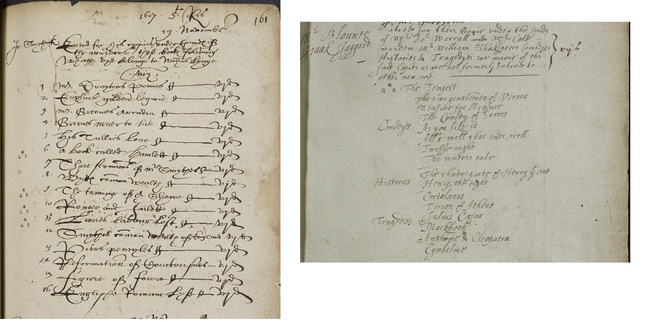

We start with a significant entry in the Stationers' Register for the 22nd of January, 1607:

'Master Linge - Entered for his copies by direccon of A Court and with consent of Master Burby under his handwrytinge these iii copies, viz Romeo and Juliett, Loves Labour Loste, The taming of A Shrew'

There's a complicated and interesting history behind this entry that tells us a lot about evolving concepts of copyright, and the Stationers' involvement in that development.

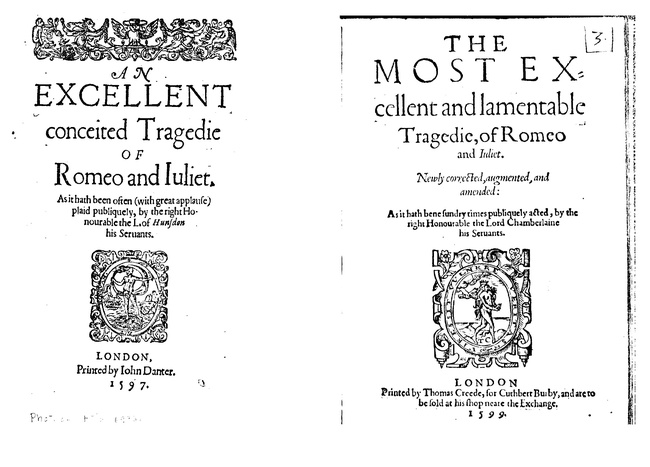

The first published edition of Romeo and Juliet was printed by Stationer John Danter. Danter had, to say the least, a chequered history with the Stationers' Company, falling foul of its rules during his apprenticeship when he was caught assisting in piratical printing. He had several more fines for disorderly printing to his name by the time he issued his rather badly printed version of Romeo and Juliet, subsequently referred to as one of the 'bad' quartos for its numerous deviations from Shakespeare's text, in 1597. Soon afterwards, in fact, his presses were seized and destroyed by the Company for further violations of the Star Chamber decrees.

A better version of the play, apparently printed from Shakespeare's own working drafts or 'foul papers', was printed by Cuthbert Burby in 1599. Burby did not register this text at Stationers' Hall - possibly because, technically, the title had already been printed by Danter (albeit with substantial textual divergences). However, this does not seem to have affected his right to transfer the title to Stationer Nicholas Ling.

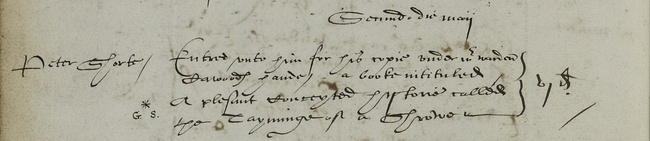

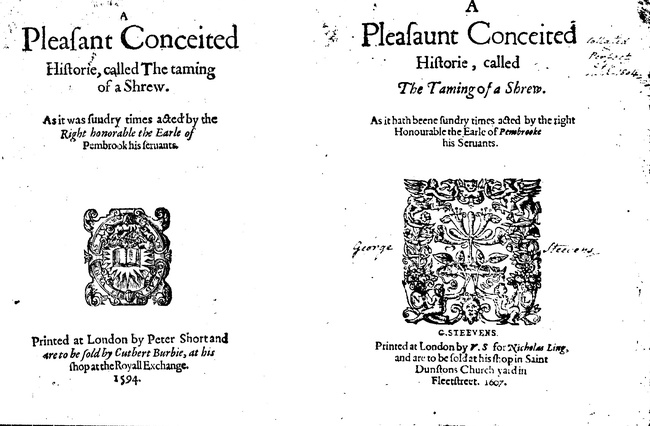

An even more complicated copyright history emerges when we look at Ling's registration of The Taming of A Shrew. This play was first printed by Peter Short for Burby in 1594, and there's been considerable debate over its relation to Shakespeare's The Taming of The Shrew.

The texts differ by considerably more than the indefinite article in the title: for a start, Christopher Sly, the character in The Shrew's framing device, has a much more significant part in A Shrew. It's possible that A Shrew is simply another 'bad' quarto, or misremembered reconstruction of Shakespeare's text, or that it's an earlier draft of The Shrew. It has also been suggested that these are simply two different versions, written by different hands, of another text which is now lost to us. Be that as it may, it's The Taming of A Shrew which Burby made over to Ling, and which was printed in 1607 by Valentine Simms.

Ling subsequently transferred The Taming of A Shrew to John Smethwick. Smethwick was part of the syndicate who published the volume of Shakespeare's work which we now call the First Folio, in 1623, and as such contributed the texts to which he owned the title; which is why Shrew is not among the 'new' titles that needed to be entered in our famous First Folio registration. However, the text printed in the First Folio is The Taming of The Shrew as we now know it - a very different text from The Taming of A Shrew acquired by Ling.

What would seem to us a very significant distinction for the purposes of copyright in terms of content (and a lesser one in terms of title) seemed to pose no problem to the seventeenth century Stationers. Revisiting these episodes gives a refreshing insight into different conceptualisations of authorship and ownership: a good way to assess our relationship with the past, and our potential for future development.