GRANT OF LIVERY

1 FEBRUARY 2021

This Day in the Archive: 1 February

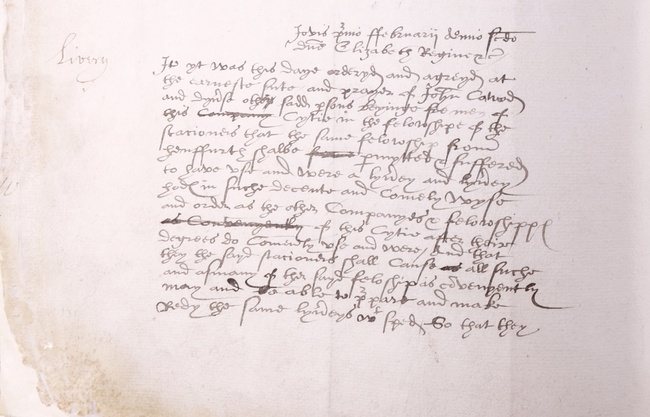

On the 1st of February 1560, the Lord Mayor of London issued a precept that ‘it was this day ordered and agreed at the earnest suit and prayer of John Cawood and diverse other said persons, being free men of this City in the fellowship of the Stationers, that the same fellowship from henceforth shall be permitted and suffered to have, use and wear a livery and livery hoods in such decent and comely wise and colour as the other Companies and followships of this City after their degrees do comely use and wear.’

Leading image: Stationers' Company Procession to St Paul's, Ash Wednesday 1968, Stationers' Company Archive

Grant of Livery was a significant step in establishing the prominence of the Stationers’ Company in the City. John Cawood, who was so energetic in pursuit of this goal, was clearly a consummate politician. Despite having served as Queen’s Printer under Mary Tudor – a position he seized when the previous King’s Printer, Richard Grafton, took an unfortunate gamble in supporting the succession of Jane Grey – he managed to secure a role as joint Royal Printer, with Richard Jugge, for Elizabeth I. Cawood went on to serve as Master of the Stationers’ Company from 1561 to 1563, and again for 1566-67.

Transcription of Lord Mayor's Order, Liber A f4v

To appreciate the full implications of the Grant of Livery, it’s worth remembering that between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, clothing in England was closely regulated by a succession of sumptuary laws. These dictated not only which articles of clothing a person could wear, but also which style, fabric and colour, according to their rank. The sumptuary laws served the dual purpose of demarcating people’s social status, and controlling the import of foreign textiles. References to the sumptuary laws abound in Shakespeare: for instance, Rosaline’s remark in Love’s Labour’s Lost that ‘better wits have worn plain statute-caps’, refers to a 1571 decree that all men beneath a certain rank should wear flat caps on Sundays and holidays, in an attempt to promote the consumption of domestic wool.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London: 'Wool, knitted and fulled, with layered brims, English, 1500s'

Our Company Archives contain valuable evidence of how Livery Companies participated in this regulation of apparel. Copied into Liber A is an Order of Common Council from 1582, prohibiting Company members from wearing ‘lace or otherwise any gold or silver or embroidered or tailor’s work like to embroidery or lace made of or with any metal’ (Liber A, f42r). A transcription of an order from the Court of Aldermen in 1619, lamenting the poor quality of fur trimmings on livery gowns, is helpfully followed by a note on the prices of different kinds and qualities of fur (Liber A, ff96r-96v; the ‘chief Companies’ apparently favoured martens’ fur).

Subsequent Court Orders rebuke Liverymen for various sartorial misdemeanours. I was particularly struck by the minutes of a Court meeting of 1 July 1635, lamenting that several members of the Livery ‘have upon solemn days of Meeting repaired unto the Hall and other places wearing falling bands, doublets slashed and cut, with other undecent apparel, which at such times we conceive ought not to be done as not fitting with the habit of citizens.’ Searching the Victoria and Albert Museum’s fantastic online image collection helped me to visualise this a bit better. ‘Slashing’ doublets began as a way of circumventing the restrictions of Elizabethan dress: cuts in the sleeves allowed the wearer to show off the colourful fine silk of their linings.

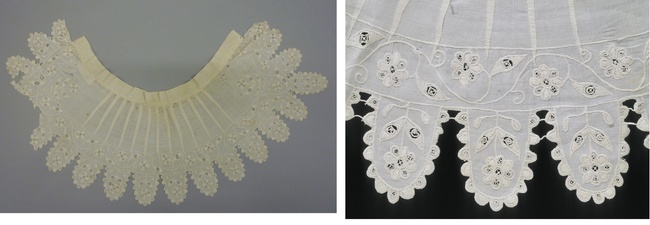

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London: 'Man's linen falling band, 1625-50, English; embroidered with cutwork, floral, whitework'

Falling bands were wide, flat collars, introduced in the 1590s as a cheaper and more informal alternative to the ruff. By the 1630s, the fashion was for a large falling band: to give you an idea, the example shown here has a depth of 25cm from the neckband to the tip of the scallop! Hardly discreet items, then, and one can’t help having some sympathy with the Court’s decision to fine Liverymen for wearing one to the funeral of a fellow Stationer.